Likes, Shares, and Side Effects: Misinformation’s Effects on Health

Source – Authors In today’s era of information access and AI, it is becoming increasingly difficult to separate truth from well-made AI-generated content. Identifying AI becomes especially challenging because people aren’t usually in a discerning mindset when scrolling through the internet. Most of the time, they’re simply looking to relax and be distracted. That might be (debatably) fine when it comes to funny videos or memes, but it’s a very different story when health information is involved. It is now common for people to look up what help they need before they go to a doctor. This information helps them identify the type of care they receive, its costs, and how to exercise home remedies before they need to go to a medical professional. It follows that they must be informed with information that’s accurate, relevant, timely, up to date, and transparent. However, because of limited skills to access good quality health information, people tend to rely on information derived from social media, friends, and, increasingly, AI tools like ChatGPT. Online platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram are common sources of fast and easy information; however, this space also propagates harmful practices as they may provide people with misleading or biased, inaccurate, and poor-quality health information. This practice of misinformation (false or inaccurate information deliberately intended to deceive) and disinformation (deliberately misleading or biased information; manipulated narrative or facts; and propaganda) is one of the most rampant problems in healthcare that affects our generation. The situation has escalated to the point that healthcare systems’ efforts to eliminate life-threatening diseases have been severely impacted. In the Philippines, a state of panic broke out in 2019 following the re-emergence of polio, a disease previously declared eradicated in the country. This resurgence was closely linked to the widespread misinformation stemming from the dengue vaccine “Dengvaxia” controversy in 2017, where exaggerated claims about vaccines causing severe side effects or even death led to a sharp decline in public trust in immunization programs. As a result, misinformation became a key barrier to polio eradication efforts, with fear and vaccine hesitancy hampering the country’s disease prevention campaigns. To this day, low public trust in vaccination continues to affect routine immunization efforts, shown by a childhood immunization rate of 61%, far below the 95% target, leaving many children vulnerable to otherwise preventable deadly diseases. At the same time, while AI-powered tools offer unprecedented access to knowledge, their downsides must not be overlooked. AI models generate content based on vast datasets, but they do not inherently distinguish fact from fiction. Without proper verification, public information may be based on AI hallucinations. This complicates people’s ability to find genuinely evidence-based health information, which in turn may affect their health-seeking behavior. If individuals begin to mistrust physicians or delay consultations because of inaccurate online advice, the doctor–patient relationship may weaken, leading to poorer adherence to medical advice and potentially worse health outcomes. On the bright side, these infodemics and misinformation can be effectively addressed through multisectoral initiatives implemented at both macro and micro levels. While government interventions of developing legal measures and policies in the scene are essential, corresponding support must be provided in youth and community settings. Campaigns should aim to create awareness, improve health-related content, build trust in credible health organizations and experts, and generally enhance people’s literacy in both digital and health aspects for them to better assess and identify misinformation. Young people play a pivotal role in this dynamic landscape. With their strong online presence, young people are often the first to encounter, share, or challenge health-related content. Their digital fluency enables them to quickly amplify both accurate and inaccurate information. Harnessing this potential requires targeted interventions that empower youth to become responsible digital citizens. Training programs, peer-led campaigns, and collaborations with student and youth organizations can help shape a culture of critical thinking and fact-checking. Several global and local initiatives provide examples of how to effectively combat misinformation. For instance, the S.U.R.E. campaign in Singapore effectively combined government messaging, media partnerships, and youth ambassadors to promote fact-checking habits. Similarly, in the Philippines, UNICEF worked with Meta to analyze vaccine hesitancy trends and organize campaigns to increase confidence in routine vaccination. These examples highlight that coordinated strategies combining digital literacy, community engagement, and credible messengers can mitigate the harms of misinformation and restore confidence in healthcare. As the world grapples with the double-edged sword of digital and AI-driven information, safeguarding public health depends on more than just regulation. It requires a culture of discernment, responsibility, and trust. AI and social media will remain central in how people access health knowledge, but the key lies in empowering individuals, especially the youth, to navigate this landscape wisely. Let’s utilize the strategies offered by successful case studies and foster collaboration across sectors and societies to ensure health communication’ purpose: to inform, protect, and improve lives. About the Authors Bill Whilson Baljon Policy and Community Partnerships Bill Whilson Baljon is a pharmacist and public health advocate from the Philippines. He is dedicated to promoting health equity and empowering communities through his work in health promotion, policy advocacy, and community engagement. Abigail Salen Visual and Content Manager Abigail Salen is a multimedia artist from the Philippines. She aims to utilize visual communication in health promotion and sustainable development, all dedicated to design for good. They are the co-founders of Yay! I’m Sober, a health awareness initiative in the Philippines that engages youth, businesses, and civil society organizations to encourage tobacco and alcohol cessation using youth-driven, inclusive, and supportive messaging.

From Fragmentation to Alignment: Redesigning Global Health Architecture for 2030 and Beyond

Image source – A. Vesakaran on Upsplash The COVID-19 pandemic triggered the largest surge in global health financing in recent history, prompting pledges of reform and solidarity across nations, donors, and institutions. Five years later and just five years before the end of the Sustainable Development Goals timeline in 2030, critical questions remain: Has global health architecture truly evolved? Are countries more prepared and in control of their health systems? Evidence from the Global Health Expenditure Database (April 2025) reveals that low-income countries still rely heavily on foreign aid, which accounts for more than 25% of their total health expenditure. In contrast, government expenditure on health remains low, with most countries allocating less than 10% of their national budgets to the sector. Despite repeated commitments, including the Abuja Declaration’s 15% target, domestic financing remains inadequate, and health systems continue to underperform. Systemic Challenges • Donor Overreach and Parallel Systems: Donor funding often flows through fragmented vertical programs (e.g., HIV, malaria, immunization), bypassing national health strategies and creating duplication. This undermines long-term sustainability and weakens institutional capacity.• Lack of Coherent Governance: There is no binding global framework to hold donors accountable to national priorities. Despite efforts such as the Lusaka Agenda and updates to the International Health Regulations (IHR), donor coordination remains voluntary and inconsistent.• Neglect of Primary Health Care: According to GHED data, less than 30% of government health spending in many low- and middle-income countries is allocated to primary health care. Instead, spending is concentrated on curative services and disease-specific interventions, leaving frontline systems underfunded.• Weak Integration of Evidence into Decision-MakingDespite growing access to global guidance and data, many countries still face challenges in translating evidence into policy and practice. Capacity gaps in data analysis, health economics, and implementation science often due to underinvestment in local institutions, limit the ability to make strategic choices, assess trade-offs, or negotiate effectively with external partners. What Reform Should Look Like • Legally Binding Frameworks for Donor Coordination:Integrate donor alignment and transparency requirements into global governance instruments such as the International Health Regulations. Donors should be obligated to report funding through national health accounts and align with country-led strategies. • Country-Led Health Investment Compacts:Shift from fragmented projects to co-financed national health compacts, where governments and development partners co-develop health system investment plans. These compacts should be reviewed publicly and embedded in national budget and monitoring frameworks. • Strengthen Regional Leadership and Sovereignty:Empower regional organizations such as Africa CDC, WAHO, and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Health Desk to lead pooled procurement, local pharmaceutical regulation, and cross-border surveillance. Establish continental public dashboards for health security financing. • Rebalance Spending Toward System Foundations:Redirect funding toward primary care, community health workers, health infrastructure, and public health surveillance. Governments should recommit to the Abuja target of allocating at least 15% of their total budgets to health. • Fund Southern Institutions and Knowledge Platforms:Increase investment in Africa-based research institutions, policy think tanks, and civil society groups to ensure global policy and guideline development reflects the realities and leadership of the Global South. Conclusion The architecture of global health remains tilted toward external control, vertical programs, and fragmented governance. Reform must go beyond temporary initiatives or rhetorical solidarity. It must be rooted in enforceable rules, long-term financing, regional agency, and country-driven accountability. With just five years left to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, the time to shift power, rebuild trust, and design a resilient, equitable, and accountable global health system is now. References World Health Organization. (2025) Global Health Expenditure Database (GHED): April 2025 Release. https://apps.who.int/nha/database The Future of Global Health Initiatives (FGHI) Report. (2023) A vision for evolution: Aligning GHIs with country systems. https://www.futureofghis.org Kickbusch, I., & Aginam, O. (2021). Reforming the Global Health Architecture: The Road to Equity and Effectiveness. Geneva Global Health Hub. https://www.g2h2.org/posts/reforming-global-health-architecture Center for Global Development. (2023). It’s Time to Change: Reforming the Global Health Architecture. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/time-change-reforming-global-health-architecture World Health Organization. (2024). Strengthening the Global Architecture for Health Emergency Preparedness, Response and Resilience (HEPR). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060616 United Nations. (2023). Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals: Report of the Secretary-General. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023 Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). (2022). New Public Health Order for Africa. https://africacdc.org/download/the-new-public-health-order-for-africa Marten, R., & Smith, R. D. (2023). Power shifts in global health: Are we there yet? BMJ Global Health, 8(1), e010248. https://gh.bmj.com/content/8/1/e010248 About the Author Ebunoluwa Ayinmode Program Manager Ebunoluwa Ayinmode is a global health professional and Program Manager at WAFERs. Her niche is health systems, guidelines, and policy. She champions locally driven strategies and amplifies African voices in global health, bridging diplomacy, data, and grassroots action.

World Humanitarian Day 2025 Blog

Image source – Tim L. Productions on Unsplash Shielding the Frontline: Diplomacy for Protection of Humanitarian Health Workers Introduction The year 2024 witnessed a grim record for attacks on humanitarian health workers globally, with 377 aid worker fatalities across 20 countries, a staggering 137% increase from 2022. The trend continues in 2025 with 545 attacks impacting facilities and 412 attacks affecting personnel between 1 January and 19 August 2025. Amidst total fatalities in conflict-affected situations, the local and national humanitarian and health workers bear the greatest burden of violence, accounting for 90 per cent of victims. The protection of humanitarian health workers has become a critical concern in the international humanitarian law and policy discourse. As the world observes World Humanitarian Day 2025 under the theme “Strengthening Global Solidarity and Empowering Local Communities,” the protection of humanitarian health workers has emerged as a critical nexus where international cooperation and local empowerment must converge. There is an urgent need for enhanced protection mechanisms through health diplomacy for those in vulnerable situations and exposed to increased risk of attacks, while providing medical care in conflict zones and humanitarian emergencies. Evolving Nature of Attacks Modern conflicts have witnessed a distressing evolution in the targeting of healthcare infrastructure. Unlike traditional warfare, where International Humanitarian Law was respected and protecting medical facilities was prioritized, contemporary conflicts increasingly employ healthcare destruction as a means for disrupting the health ecosystem. The attacks manifest in various forms, from direct bombing of hospitals and ambulances to more subtle tactics such as deliberately targeting energy and water infrastructure vital to the functioning of the healthcare system. For instance, it has been witnessed that the attack on health have seen a notable increase in the use of explosive weapons from 36% in 2023 to 48% in 2024. Armed drone attacks on healthcare facilities have similarly increased from 9% to 20% over the same period. This systematic targeting of healthcare providers requires international attention and action to prevent such incidents and uphold International Humanitarian Law (IHL). International Frameworks in Place Global solidarity for health worker protection encompasses diplomatic coordination, shared intelligence, and collective advocacy that can shield health workers from attack. While the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and International Humanitarian Law provide robust legal foundations for humanitarian and healthcare personnel protection, active measures have been taken since 2012, with the World Health Organization (WHO) creating a surveillance database on Attacks on Health Care. Following this, in 2014, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2175, and in 2016, Resolution 2286 to protect humanitarian workers, health personnel, and medical facilities in conflict zones, respectively. In 2020, the WHO launched the Health Worker Safety Charter, which called key stakeholders to be involved in ensuring protection from violence, physical and biohazards, improving mental health, developing national programs, and emphasizing the synergy of health worker and patient safety. The role of physicians and other health workers in the preservation and promotion of peace is established in WHOs Resolution WHA 34.38, that establishes the role of WHO in facilitating the implementation of UN Resolutions towards peace and conflict prevention. The Global Health and Peace Initiative furthers the Humanitarian-Development-Peace nexus underlines the role of health as a key driver of peace and sustainable development, including all parts of the UN and the World Bank in conflict prevention, mediation, and resolution. However, despite these measures, the attacks on humanitarian and health workers continue, highlighting the need for more effective collective action. To address this concern, diplomatic mechanisms that can translate international solidarity into tangible protection for health and humanitarian workers, and protection of health facilities are needed. This was reiterated by the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, in his message on the Call for Action to protect humanitarian workers, by stating the need for political will and the need to invest in their safety. Challenges to address Significant resource disparities persist between international and local health worker protection initiatives. Humanitarian and health workers representing international humanitarian organizations have access to security training, evacuation procedures, insurance coverage, and protection that are unavailable to local health workers. Additionally, the paucity of humanitarian health education and training programs in conflict-affected countries restricts local health workers’ access to specialized protection training that could enhance their safety. Many global solidarity initiatives inadvertently impose external priorities, timelines, or methodologies that conflict with community preferences or cultural norms. Local healthcare communities’ voices are underrepresented in the global discourse around their protection; that leads to a narrative and solutions facing glaring implementation challenges. Integrating global solidarity with local empowerment requires inclusive coordination mechanisms that can balance an international response with local context-specific solutions. To address this, it requires diplomatic frameworks that can maintain global solidarity while ensuring meaningful local participation in health worker protection decision-making. Diplomacy: Bridging Global Solidarity and Local Empowerment Effective diplomacy can integrate global solidarity and local empowerment for humanitarian and health worker protection. Multi-track diplomacy between nations, multistakeholder engagement involving various actors, and informal field-level negotiations are needed to bring about this balance and address this urgent objective. However, in conflict settings, prominent diplomatic channels often harness negotiation, mediation, and advocacy to ensure access to affected populations, raise protection issues, and influence domestic actors impeding humanitarian relief. Current diplomatic efforts must go a step further to bring local health worker community perspectives into mainstream policy and negotiation efforts to ensure securing the space for health interventions while engaging politically and socially to empower local capacity. For instance, humanitarian organization like the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) regularly bring local humanitarian health workers into the process of negotiating policies that ensure access and protection for healthcare communities in highly insecure environments. Successful protection strategies require trust-building, multi-level engagement, evidence-based advocacy, and innovative protection mechanisms. For instance, the synergy of global solidarity and local empowerment was witnessed when UNICEF, as an international organization, negotiated for corridors of peace and days of tranquillity in Syria and Yemen, specifically designed to allow immunization campaigns, human resource training, ensuring the continuous supply of vaccines, and supporting community engagement

More Than Medications: The Role of Pharmacists in Medical Device Counselling

It has often been the case that, when people imagine a pharmacist, they picture someone behind the counter, dispensing medications and offering advice on prescriptions. But in today’s modern healthcare landscape, pharmacists are stepping into a more expanded role—one that goes beyond medications to include preventive care and health monitoring. In line with this, as noncommunicable diseases are still the leading cause of global mortality, it is becoming more common for patients to use medical devices to monitor and take care of their health. That’s an area where pharmacists can come in, as having medical devices isn’t enough—knowing how to use them correctly is equally important, if not more. Pharmacists are recognised as the most accessible healthcare professionals, often the first to see patients with health concerns. Whether it’s a quick blood pressure check at the pharmacy or a discussion about managing blood sugar, pharmacists play a key role in educating patients about their medications and the medical devices that will help them stay healthy. For instance, patients newly diagnosed with diabetes are likely instructed to monitor their blood sugar, but without proper guidance, they might struggle with using a glucometer and end up with inaccurate measurements. A pharmacist who can counsel and demonstrate their use will ensure the patient avoids errors and unnecessary complications. Yet, despite this crucial role, many pharmacists may not be getting the training they need. A study among graduating BS pharmacy students in Metro Manila, Philippines, found that a significant number had limited knowledge of diabetes management devices, as 51.89% had low knowledge with insulin syringes, 26.89% with insulin pens, and 12.26% with glucometers. These numbers highlight an opportunity to integrate more optimized education and training. To equip pharmacists with the necessary skills, pharmacy education must evolve. Some suggestions that can be done include: Curriculum Integration – Medical devices should be a core part of the pharmacy curriculum, with dedicated lessons on their function, proper use, and troubleshooting. Hands-On Training – Practical experience with medical devices should be a standard part of pharmacy education, focusing on technique and counselling. Ongoing Learning – Pharmacists should have access to workshops, certifications, and continuous professional development focused on medical device counselling, factoring in the differences of medical devices per manufacturer. As healthcare shifts toward prevention rather than just treatment, pharmacists also have a role to play. By knowing salient points of both medication and medical device counselling, they can further empower patients to take charge of their health. At the end of the day, a pharmacist’s job isn’t just about handing over the medicines listed in a prescription, they make sure that patients have the knowledge and confidence to manage their health effectively. About the Author Bill Whilson Baljon Public Health Advocate Bill Whilson Baljon is a public health advocate from the Philippines. He is dedicated to promoting health equity and empowering communities through his work in health promotion, policy advocacy, and community engagement.

Against the Odds: The Pandemic Agreement’s Path to Consensus

Introduction After more than three years of intense negotiations, WHO Member States reached a historic milestone on April 16, 2025, by finalising the pandemic agreement. As WHO member states prepare for the adoption of the “greened” or agreed legal text at the 78th World Health Assembly, it’s worth reflecting on how governments and non-state actors such as civil society organisations and academia have worked to enable success. While entire books can be written to illustrate what it took for the pandemic agreement to be finalized and serve as a foundation for preventing, preparing for and responding to pandemics, in this blogpost I will share highlights, from FOUR PAWS’ perspective as one of the many “relevant stakeholders” in the negotiation process. The Challenges Finishing a treaty in record time The challenge was to finalise an international multi-issue pandemic agreement in record time during an ongoing global health crisis, amid geopolitical tensions and in a UN body that is not a common ecosystem for international treaty negotiations. Member States set the goals of strengthening the international health regulations on the one hand, while also introducing a complementary legal framework to address gaps in pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. WHO member states took this decision out of necessity, not only to fill the gaps in the global health architecture but to set themselves on a better path than the one they experienced during the pandemic. Expanding the scope of what prevention means While FOUR PAWS was active in several international policy processes, the World Health Organisation was not yet a typical space within which we, as an animal welfare organisation, were present before the pandemic. However, the pandemic made one thing clear: governments cannot fulfil their promise to effectively prevent pandemics without addressing human activities that drive pandemics at the human-animal-environment interface. This realisation, echoed by many non-governmental organisations, experts and institutions, led FOUR PAWS and others from the animal welfare and conservation sector to engage. The scope we considered necessary was not part of the standard measures which public health policies tied to pandemics typically addressed. Traditionally, the focus of the public health sector was on emergencies and the stage after the outbreak. However, when WHO Member States decided to negotiate the pandemic agreement, they added “prevention” and a whole of government and whole of society approach to the scope of the agreement. This was a welcome move. Interventions had to take place at the earliest stage of disease emergence, before communities suffered deadly outbreaks and before public health institutions were confronted with an emergency. Addressing and integrating that policy gap into an international public health debate – within a pandemic agreement that also needed to prioritise health system capacities, pandemic-related health products, and support for implementation and financing, while simultaneously updating the International Health Regulations – was, to put it mildly, very ambitious. Civil society’s access to the negotiations Compared to other international processes, the pandemic agreement negotiations generally offered limited access to CSOs, which made effective engagement a challenge. In other international negotiations, observers have access to the actual negotiation sessions and several spaces to engage with member states. This makes advocacy efforts more effective, as it gives civil society real-time insights into member states’ priorities and concerns, the reasoning behind their positions and an idea on areas where evidence or analysis is needed – ultimately leading to the best use of member states’ and civil society’s time. The ingredients Jenga diplomacy: balancing evidence, dialogue and compromise During the first rounds of the pandemic agreement negotiations, early participation was restricted to online statements during opening and closing sessions. Thanks to persistent advocacy by a few member states and civil society champions, our access to the process gradually increased. Before the 7th Intergovernmental Negotiating Body Session in October 2023, which was the first session when “Relevant Stakeholders” were granted in-person access to the WHO building during the negotiations, our engagement with member states was through policy briefs, bilateral meetings with diplomats and events which member states co-hosted with us. In those interactions, member states shared their challenges, challenged our assumptions, flagged gaps and obstacles, asked for expertise, and guided us on how to be more effective. Throughout the process, despite their differences, we noticed a collective unwavering commitment among diplomats to unlock obstacles. Bridge-building countries, experts and civil society organisations all took the initiative to convene a dialogue, which was conducive to trust-building. This mutual exchange gave us much-needed reality checks, helped us identify academic institutions and allies who were also ready to work with member states to advance the process. Access to the WHO building during the negotiations in late 2023 brought with it a new layer of valuable insights. After several rounds of negotiations, the Bureau’s draft evolved into a member-state-owned text. Just observing which groupings were convening jointly or alone at the building showed us a progression in the interregional dynamics. While in the earlier stages, only a few member states engaged in informal dialogue with member states from other regions, with time, we saw an encouraging increase in outreach and a growing number of interregional huddles as the process advanced. While relevant stakeholders were not allowed to observe the actual negotiations, even after we had access to the building, opportunities including meetings with the Bureau, daily statements in the mornings in plenary, and the possibility in the final negotiation sessions, of hosting side events inside the WHO at a meeting room that was made available for non-state actors were spaces where we could also share our observations and concerns in real time. Interestingly, our participation at the margins of the negotiations and member states’ willingness to engage with relevant stakeholders often gave us a more complete understanding of the positions and flexibilities than what member states shared in the formal negotiation sessions. The Bureau and member states called on CSOs to be constructive and support in advancing the process, which we were increasingly better positioned to do. Stakeholders, including academia, think tanks, CSOs, and member states,

Addressing the Need for Global Public Health Priority of Skin Diseases

Côte d’Ivoire, together with Nigeria, Togo, Micronesia, China, Colombia and Egypt, is leading an initiative to position skin diseases firmly on the global public health agenda by proposing a World Health Assembly Resolution on “Skin diseases as a global public health priority”. Stimulated by the Universal Health Coverage framework (SDG indicator 3.8.1), a coalition of civil society organisations, including patient groups, healthcare professionals, academia, and philanthropists, has been advocating to reduce the burden of skin diseases globally. These groups are: International Alliance of Dermatology Patient Organisations (GlobalSkin), International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS), International Foundation for Dermatology, Health Diplomacy Alliance, Anesvad Foundation, Geneva University Hospitals, Neglected Tropical Disease NGO Network, Skin Cross-Cutting Group, World Skin Health Coalition. [Add photo of logos] Impacting an estimated 2 billion people globally, skin diseases and wounds affect individuals of all ages and are one of the most common reasons for seeking medical help. Yet, they remain disproportionately neglected in national and global health priorities. Despite their widespread impact, skin diseases are often not prioritised due to their primarily non-fatal nature, resulting in serious health and economic consequences. The effects of skin conditions extend beyond physical suffering, including social stigma, mental health impacts, and lost productivity, exacerbating inequalities, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Skin diseases are increasingly influenced and exacerbated by climate change, affecting the most vulnerable in society. Previous initiatives at this level have targeted individual conditions. It is now time to combine these efforts. An integrated strategy will improve health outcomes, access to care, and treatment, particularly for vulnerable populations. WHO 156th Executive Board – Skin Diseases as a Global Health Priority The 156th Executive Board meeting of the World Health Organisation was held February 3-11, 2025, in Geneva. Deliberations on skin diseases took place on February 5 & 7, highlighting the growing recognition of skin diseases as a global health priority. On February 10, 2025, the 156th WHO Executive Board recommended that the WHA Skin Diseases Resolution proceed for adoption at the 78th World Health Assembly in May 2025. What will a WHA Resolution on Skin Diseases Achieve? The Skin Diseases Resolution is focused on all skin diseases , including allergies, inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases, genetic diseases, vascular diseases, cancers, infections (viral, bacterial and fungal) and rare autoinflammatory diseases. It prioritises the perspectives of patients and their caregivers in all aspects of planning and implementation. Key aspects of the Resolution: Development of a Global Action Plan to establish a framework for addressing skin diseases globally, focusing on prevention, early detection, effective treatment, and long-term care, with specific targets. Calls for dedicated health investment to expand expertise through training, particularly among primary health care workers, enabling timely diagnosis and effective support for those living with skin diseases. Supports the expansion of research, surveillance and data collection to provide innovative diagnostic tools and new treatments. Promotes equitable access to cost-effective, affordable and high-quality treatment Supports integrated services for skin diseases into current disability, rehabilitation and mental health policies More Support is Needed! Resources have been developed to support civil society in effectively advocating for the adoption of the draft Resolution on Skin Diseases at the 78th World Health Assembly in May 2025. Leading up to and onsite at the WHA78, this campaign seeks to galvanise international support for a Resolution that would drive investment in resources, research, and healthcare interventions. The core campaign objective is to raise awareness about the Skin Diseases Resolution and garner support from Member States to advance this important cause. Support the Campaign. Side-Event during WHA78 A high-level event will be held during the week of the 78th World Health Assembly, Tuesday, May 20, 2025, at 18:00 – 20:00. Registration link This critical in-person discussion will centre around the groundbreaking resolution, “Skin Diseases as a Global Health Priority”. Traditionally overlooked due to their non-fatal nature, skin diseases impact over 2 billion people worldwide, significantly affecting quality of life and economic productivity. This resolution, led by Côte d’Ivoire and co-sponsored by Colombia, China, Egypt, Micronesia, Nigeria, and Togo, marks a transformative shift in global health policy, advocating for an integrated, patient-centred response to skin health. This event will explore how the proposed resolution: ✔ Recognises the broad impact of skin diseases—beyond their medical symptoms, they impose substantial social, psychological, and financial burdens. The resolution promotes holistic care that addresses stigma, mental health, and patient well-being. ✔ Strengthens primary healthcare systems by urging Member States to integrate skin care into routine healthcare services, enhance diagnostic capabilities, and invest in healthcare workforce training. ✔ Mobilises resources and innovation—calling on governments, donors, and civil society to fund sustainable solutions, including digital diagnostics and teledermatology, to reach underserved communities. ✔ Ensures sustained global action—encouraging ongoing dialogue, national action plans, and regular updates at the World Health Assembly to adapt to emerging challenges, including climate-related skin health concerns. Conclusion Improving skin health globally requires integrated care models that include dermatological management, wound care, prevention of loss of function, and mental health support. Investments in training healthcare workers, particularly on the frontline, and research into social determinants of skin diseases are essential. Advocacy and funding should enhance research capacity, develop diagnostic tools and treatments, and expand skin health databases to optimise resource allocation and evaluate interventions. Addressing the impact of climate change on skin health through tailored research and healthcare provider training is also critical. These efforts aim to achieve “Skin Health for All,” improving health outcomes and economic productivity by addressing the medical and socioeconomic impacts of skin diseases worldwide. By working together, we can ensure the adoption of the Skin Diseases Resolution and prioritise skin health for all. Acknowledgements: Much gratitude to Côte d’Ivoire and co-sponsors Colombia, China, Egypt, Micronesia, Nigeria, and Togo for their leadership in making skin health a public health priority. The International Alliance of Dermatology Patient Organisations (also known as GlobalSkin) is a unique global alliance, committed to improving the lives of skin patients worldwide. We nurture relationships with members, partners and all involved in healthcare, building dialogue with decision-makers around the globe to promote patient-centred healthcare. GlobalSkin works to empower its more than 320 patient association members ─ located in 74

Mental Health Cyberdiplomacy in the Age of Algorithmic Trauma

What if the most potent threats to mental health no longer emerge from violence—but from the screens we hold in our hands? As digital weapons evolve to target not just systems but minds, mental health diplomacy must either transform—or become obsolete. The global mental health community can no longer afford to treat cyberspace as outside its remit. Psychological warfare is no longer metaphorical. It is algorithmic, ambient, and deliberate—disabling not the body, but the will. In my article “Advancing global mental health diplomacy through a rights-based approach”, published in The Lancet Psychiatry (Volume 12, Issue 4, pp. 247–249, April 2025), I proposed a redefinition of global mental health diplomacy—shifting it from ad hoc technical cooperation toward a strategic, rights-based pillar of international relations. I argued that diplomacy for mental health must not only promote service access, but protect psychological integrity, uphold dignity, and reinforce system-wide resilience. That article laid the foundation. But it is in the digital terrain that this diplomacy now finds its most urgent frontier. Mental health cyberdiplomacy is the next step. It responds to a new class of threat—where trauma is no longer transmitted only through direct violence, but through information flows engineered to destabilise, disorient, and divide. This is no longer about technology alone. It is about how trauma travels, how trust dissolves, and how fear is weaponised—not just across borders, but across timelines, across generations. Traditionally, cyberdiplomacy has focused on infrastructure, sovereignty, and the governance of data flows. It was never built to address psychological safety. Yet in today’s digital theatre, emotional disruption has become an instrument of statecraft. Disinformation campaigns, synthetic media, and algorithmic manipulation are now deployed to fracture perception, destabilise identity, and erode public sanity. Minds are no longer merely influenced—they are targeted. Emotions are triggered at scale. And the consequences for mental health are no longer speculative. We are witnessing the rise of a new psychological condition: geopolitical anxiety—a state of digitally mediated distress induced not by direct exposure to violence, but by ambient proximity to crisis. Endless feeds of war, collapse, and catastrophe create a recursive sense of helplessness. People are not merely observing the world unravel—they are experiencing it internally. Clinical symptoms—emotional numbing, sleep disruption, suicidal ideation—are surfacing among those never physically near the trauma. This is a new category of harm: cumulative, distributed, and algorithmically delivered. Some institutions have begun to recognise this mental toll. There are cautious moves toward regulating harmful content, improving digital literacy, or embedding psychosocial elements into public discourse. But these efforts remain fragmented. They are reactive rather than strategic. They respond to symptoms, not systems. They signal awareness, but lack cohesion, scope, and diplomatic reach. What emerges is not a framework—but a vacuum. Mental health cyberdiplomacy does not describe what already exists. It proposes what must. We need a new diplomatic architecture—one that embeds psychological protection into the governance of cyberspace. This architecture must be multidimensional and anticipatory. It must operate across four strategic axes: Representation – Mental health must be positioned at every cybernorm table: from the UN Open-Ended Working Group to the Global Digital Compact. Psychological safety must be recognised as a pillar of digital governance, no less than infrastructure integrity or data protection. Accountability – Platforms and algorithms must be held to standards that prevent the amplification of trauma and the normalisation of emotional harm. Independent auditing, algorithmic transparency, and trauma-informed digital design must become standard, not exceptional. Law – Psychological operations that intentionally destabilise populations must be named and framed as violations of international law. This is not merely cybercrime. It is psychological targeting. And its costs are collective. Resilience – Cognitive preparedness, emotional immunity, and digital mental health literacy must be embedded into education, civic infrastructure, and crisis response. These are not soft skills. They are core elements of democratic durability. Mental health cyberdiplomacy must operate across the full arc of crisis: preparing systems before conflict, defending psychological integrity during it, and supporting trauma-informed recovery afterward. It must be present where systems are stressed, where fragmentation is accelerating, and where minds become theatres of geopolitical contestation. The foundations are already in place. The WHO QualityRights framework, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and the WHO Mental Health Action Plan articulate a vision of rights-based, person-centred mental health systems. My Lancet Psychiatry article called for these tools to be interpreted not only as health policy instruments, but as diplomatic assets—capable of shaping global norms and enabling systemic protection against psychological harms. But without an extension into the cyber domain, that protection remains incomplete. Unprocessed trauma is not neutral. It compounds over time. It corrodes public trust, destabilises institutions, and accelerates radicalisation. In an era defined by ambient fear and engineered outrage, defending the mind is no longer a clinical concern. It is a geopolitical imperative. This is not about sanitising the internet or regulating emotion. It is about preserving the conditions that make peace and democracy viable. In a hyperconnected world, the battlefield is cognitive. And in that battlefield, mental health is no longer a background issue. It is a strategic domain. Diplomacy must evolve to meet that reality—not incrementally, but systemically. If we fail to embed psychological protection into the infrastructure of our digital societies, we risk raising a generation fluent in fear, numbed to violence, and uncertain of what is real. We have built firewalls to defend our systems. Now we must build firewalls to protect our minds—from manipulation, from fragmentation, and from algorithmic despair. This strategic evolution also informs the development of MHPSS-C—Mental Health and Psychosocial Support integrated with Cyberresilience—a new operational model I have proposed to address the intersection of psychological vulnerability and digital threat. The framework, detailed in a forthcoming policy brief, aims to operationalise protection where trauma, code, and cognition now converge. Mental health cyberdiplomacy begins here—not as a reaction, but as a new logic. Not as a commentary, but as a call to reimagine how we safeguard the human condition in the digital age. About The Author

From Policy to Action: Strengthening Alcohol Control Efforts in the Philippines

Alcohol consumption is a major public health concern, contributing to significant economic, social, and health-related burdens worldwide. With approximately 3 million deaths annually, alcohol accounts for 5.3% of global mortality and 5% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The consequences of alcohol use extend beyond the individual, affecting communities, families, and healthcare systems. Alcohol is linked to various health conditions, including injuries, digestive disorders, and cardiovascular diseases. Young adults aged 20 to 39 are especially vulnerable, making up 14% of alcohol-attributable deaths. The global burden of diseases related to alcohol accounts for 5.1% of all diseases and injuries worldwide. Furthermore, alcohol-related harm extends beyond the drinker, affecting families, communities, and society at large. Beyond its health implications, alcohol consumption poses a substantial economic burden. The costs associated with alcohol-related harms contribute to financial losses, increased healthcare expenditures, and productivity declines. Studies suggest that the economic costs of alcohol-related harm account for approximately 0.01% of a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Research also indicates that higher alcohol consumption correlates with a greater disease burden, highlighting the need for stronger preventative measures to mitigate its rising economic impact. Moreover, alcohol consumption is linked to various social issues, including absenteeism, domestic violence, community disturbances, and increased mortality. It can also impose a significant burden on families, affecting the emotional, financial, and psychological well-being of caregivers, particularly spouses. Countries worldwide implement various policy interventions to address alcohol-related harms. The World Health Organization also released guidelines on how to implement alcohol control initiatives within member states such as the SAFER initiative, which encompasses the five most cost-effective interventions for reducing alcohol harm. The SAFER initiative includes activities that aim to: Strengthen restrictions on alcohol availability; Advance and enforce drink driving counter measures; Facilitate access to screening, brief interventions and treatment; Enforce bans or comprehensive restrictions on alcohol advertising, sponsorship and promotion; and, Raise prices on alcohol through excise taxes and pricing policies. Taking the Philippines as an example, it has been identified that cultural norms, aggressive marketing, and public health challenges contribute to high alcohol consumption rates. Among young people, alcohol preferences are often influenced by product type and pricing. Alarmingly, alcohol marketing has also been linked to an increase in drunkenness among students. The Philippine government has implemented several alcohol control laws such as: Sin Tax Reform Law (RA 10351), was legislated in December 2012, with the dual goals of (1) curbing cigarette and alcohol consumption, and (2) raising funds to finance the implementation of Universal Health Care (UHC) activities, programs to meet Developmental Goals, and viable alternative livelihood for tobacco farmers. Excise Taxes on Alcohol and E-Cigarettes (RA 11467), passed in 2020, increased the excise taxes on alcohol products, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), and heated tobacco products (HTPs). The additional revenue funds the Universal Health Care (UHC) efforts such as additional medical assistance and support to local governments, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act (RA 10586), enacted in 2013, penalized the acts of driving under the influence of alcohol, dangerous drugs, and other intoxicating substances. However, there are estimates, through the Philippines’ national nutrition survey, that the number of adolescents (aged 10-19 years old) who consume alcohol monthly has doubled from 2021 to 2023 – citing an alcohol epidemic within the country. This highlights a need to evaluate the current efforts and policies targeted towards reducing alcohol consumption. One of the reasons why policy efforts to reduce alcohol consumption in the Philippines face significant challenges may be the deep-rooted ties between alcohol companies and the national government. Major alcohol producers are not only key players in the beverage industry but also prominent contributors to national infrastructure projects, donation drives, and other corporate social responsibility initiatives. This likely influences major policy decisions, often tilting the scales in favor of these corporations when it comes to regulating alcohol marketing and consumption. Despite these challenges, various organizations across the country continue to push for stronger alcohol harm reduction measures. Last year, these groups united in advocating for the designation of September as National Alcohol Harms Awareness Month, established a Community of Practice with clinicians, government agencies, civil society organizations, and researchers, spearheaded studies on alcohol policies, and launched extensive information and education campaigns. Yet, political will and public support are crucial to driving meaningful change. As Filipinos often say, “Malayo na, pero malayo pa”—we’ve come far, but there is still a long way to go. The fight against alcohol harms is far from over, and now, more than ever, is the time to keep pushing forward. About the Author Bill Whilson Baljon Public Health Advocate Bill Whilson Baljon is a public health advocate from the Philippines. He is dedicated to promoting health equity and empowering communities through his work in health promotion, policy advocacy, and community engagement.

Retos y desafíos globales de la salud en personas con albinismo: Perspectiva de la República Dominicana

El albinismo es una condición genética caracterizada por la falta de melanina, lo que afecta la piel, el cabello y los ojos. Esta deficiencia no solo trae complicaciones médicas serias como una elevada sensibilidad al sol y problemas visuales, sino que también genera graves problemas sociales como el estigma y la discriminación. La forma en que se ve el albinismo varía mucho entre diferentes regiones, como en algunas áreas de África en comparación con Europa y América del Norte, lo que resalta la urgencia de abordar estas cuestiones desde un enfoque de cuidado integral. Las personas con albinismo enfrentan numerosos desafíos. El riesgo de cáncer de piel es alto debido a la falta de melanina que protege de los rayos solares, y los problemas visuales asociados con el albinismo pueden ser limitantes. Además de los retos físicos, el impacto social puede ser destructivo. En algunos contextos culturales, los mitos y malentendidos sobre el albinismo pueden provocar persecución y violencia, lo que indica que la atención médica debe considerar también el contexto social. Foto: Encuentro Anual Fundación Albinismo Solidario Asociado 2024. Es vital que la diplomacia en salud global priorice la educación y la mejora de la percepción pública como estrategias fundamentales para luchar contra la desinformación y los prejuicios asociados al albinismo. Informar adecuadamente sobre las causas genéticas y médicas de esta condición puede ayudar a eliminar estereotipos dañinos y promover un mayor reconocimiento social. Además, es importante que las políticas internacionales fomenten la creación y aplicación de medidas de protección para las personas con albinismo. Estas medidas deberían asegurar acceso a servicios médicos especializados, como la dermatología y la oftalmología, y extender las protecciones legales para garantizar la seguridad y los derechos humanos de estas personas, especialmente en las áreas donde son más vulnerables. La colaboración internacional es esencial para compartir recursos, estrategias y prácticas óptimas, y para apoyar la implementación de programas que se adapten cultural y demográficamente a las necesidades de las comunidades afectadas. Incluir las experiencias y perspectivas de las personas con albinismo en la formulación de estas políticas es fundamental para asegurar intervenciones efectivas y humanas. Con un compromiso y desarrollo continuo de estrategias de atención médica integradas, podemos avanzar hacia un futuro más justo y saludable para las personas con albinismo, eliminando barreras físicas y sociales. Un ejemplo sobresaliente de apoyo al albinismo en América Latina es la inauguración de la Primera Clínica de Albinismo en la República Dominicana, resultado de la colaboración entre la Fundación Albinismo Solidario y el Instituto ChromoMED. Inaugurada el 17 de julio de 2024, esta clínica es pionera en ofrecer un cuidado médico especializado y comprensivo en la región, dirigida por un equipo de especialistas que incluye al Dr. Carlos Gómez, la Dra. Katlin De La Rosa Poueriet, y a mí, Dr. Bary G. Bigay. Con instalaciones modernas, la clínica no solo ofrece servicios médicos de alta calidad, sino que también se dedica a mejorar la inclusión social y la concienciación sobre el albinismo, indicando un avance relevante en la creación de un entorno de aceptación y apoyo continuo. “A medida que se intensifican los esfuerzos globales por mejorar la salud de las personas con albinismo, es imprescindible reforzar la investigación en este campo. La inversión en estudios sobre terapias innovadoras, el desarrollo de tratamientos preventivos para el cáncer de piel en esta población y la creación de protocolos de atención médica adaptados son pasos esenciales hacia un futuro más equitativo y saludable. El compromiso con la educación, la investigación y la concienciación social seguirá siendo clave para garantizar que las personas con albinismo puedan vivir con dignidad y sin barreras, contribuyendo así a un mundo más inclusivo y justo.” Los esfuerzos globales por mejorar la salud de las personas con albinismo han ganado impulso en los últimos años, pero aún queda mucho por hacer. Esta población enfrenta desafíos significativos debido a la falta de acceso a cuidados médicos adecuados, especialmente en lo que respecta a la prevención y tratamiento del cáncer de piel. El albinismo, que se caracteriza por una deficiencia en la producción de melanina, expone a las personas a un mayor riesgo de desarrollar cáncer de piel debido a la mayor vulnerabilidad de su piel a la radiación ultravioleta. Por lo tanto, es fundamental invertir en investigación para encontrar terapias innovadoras que puedan reducir este riesgo y mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas con albinismo. Además, el desarrollo de tratamientos preventivos, como cremas solares de mayor efectividad y protocolos de atención médica adaptados a las necesidades específicas de esta población, será fundamental para proteger la salud de los afectados. El enfoque en la educación y la concienciación social también es clave. Sensibilizar a la sociedad sobre las realidades del albinismo, los problemas de salud que conlleva y la necesidad de inclusión social puede ayudar a reducir los estigmas y la discriminación que a menudo enfrentan las personas con esta condición. Asimismo, fomentar la capacitación de profesionales de la salud para reconocer y tratar adecuadamente las afecciones relacionadas con el albinismo es esencial. En última instancia, estos esfuerzos colaborativos en investigación, educación y desarrollo de políticas públicas son pasos esenciales hacia un futuro en el que las personas con albinismo puedan vivir con dignidad, sin barreras y tener acceso a una atención médica adecuada, contribuyendo así a un mundo más inclusivo y justo. Sobre el autor Dr. Bary G. Bigay Mercedes Director Médico Ejecutivo del Instituto ChromoMED Nacido en San Pedro de Macorís, República Dominicana, es un respetado Médico Genetista Clínico & Molecular, y Director Médico Ejecutivo del Instituto ChromoMED en Santo Domingo, Pionero en Investigación en Medicina Traslacional y Genómica del Albinismo en República Dominicana. Doctor en Medicina por la Universidad Central del Este y con especializaciones en genética y genómica en prestigiosas universidades de España y Francia como la Universidad de Valencia y la Universidad de Montpellier, posee múltiples estudios de Máster en Biología Molecular, Medicina Reproductiva y Oncología de Precisión Genómica. Es autor de importantes publicaciones científicas y ha sido reconocido

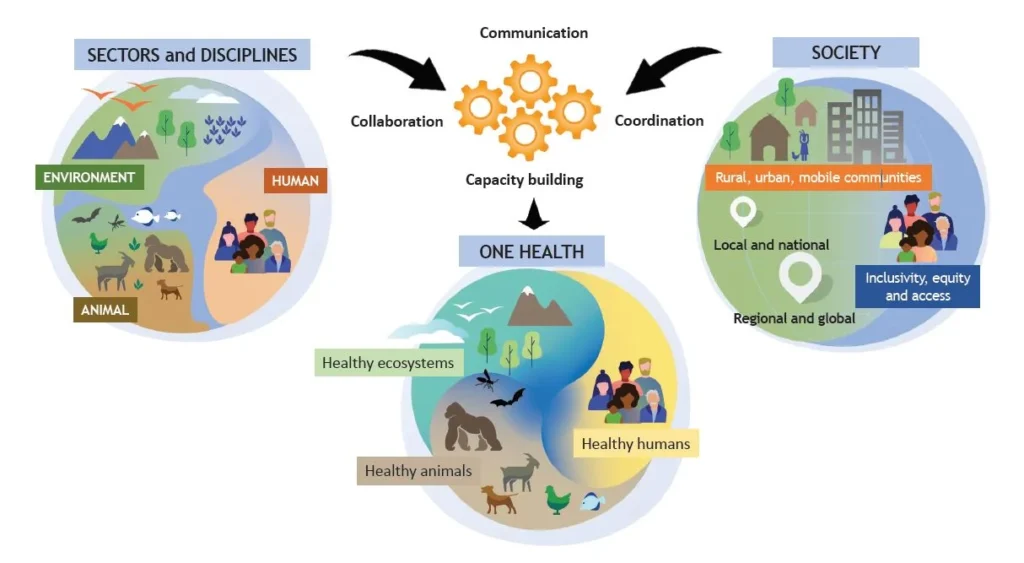

Science as Diplomacy: The Strategic Power of One Health in Global Policy

The One Health approach, which recognizes the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health, is not only a matter of scientific collaboration but also a prime example of Science Diplomacy in action. Science Diplomacy goes beyond cooperation to engage science as a strategic diplomatic tool, capable of influencing global policies, easing geopolitical tensions, and fostering trust between nations with differing agendas. Through this lens, the One Health approach becomes a means of addressing complex and often contentious global challenges by leveraging scientific expertise in diplomatic negotiations, international treaties, and conflict resolution. The diplomatic role of science becomes evident in how scientific knowledge informs global health policies, mediates disputes, and fosters international trust. For instance, pandemic preparedness is not just about sharing research and data but also about aligning different national interests in a way that can prevent diplomatic rifts during crises. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, the distribution of vaccines, access to essential medicines, and the regulation of travel and trade became highly politicized. Scientific expertise, combined with diplomatic negotiation, helped to form frameworks like COVAX that sought to balance national interests with global health equity. This balance required science to be used as a diplomatic instrument, guiding international discussions toward a common understanding of the evidence and creating mutual agreements amidst political tension. Similarly, global efforts to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) highlight the diplomatic weight science carries in policy discussions. AMR is driven by practices in agriculture, healthcare, and environmental management that are influenced by economic interests, political priorities, and social norms in different countries. Here, science provides the common ground upon which diplomatic negotiations occur. Initiatives like the Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance, developed by WHO, FAO, and WOAH, were not just scientific collaborations but diplomatic triumphs—binding nations to a shared set of guidelines that balanced national sovereignty with the need for collective action. In this case, scientific evidence served as the backbone for treaty-making, where diplomatic negotiations turned scientific consensus into political commitments. The One Health approach to climate change and environmental degradation similarly exemplifies Science Diplomacy. Environmental health directly impacts national economies, food security, and public health, making it a politically charged issue. Here, science plays a diplomatic role by creating a neutral ground for dialogue between countries that may be at odds on other fronts. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), for example, has been instrumental in shaping the Paris Agreement. Through scientific assessments of climate change’s impact on ecosystems, agriculture, and human health, the IPCC’s work serves as a diplomatic bridge, ensuring that all parties—despite conflicting political or economic interests—base their negotiations on shared scientific understanding. Science thus becomes a tool not just for cooperation but for diplomatic consensus-building, helping to mediate conflicts over resource management, carbon emissions, and environmental responsibility. In the context of wildlife conservation and zoonotic disease surveillance, Science Diplomacy plays a role in preemptive conflict resolution. Zoonotic diseases, such as Ebola and avian influenza, often emerge from regions with significant biodiversity and sometimes weak governance structures. The risk of diseases spilling over into human populations can become a source of diplomatic tension between neighboring nations or trading partners. Science can act as a diplomatic intermediary by offering objective, evidence-based assessments of the risks and by establishing internationally recognized protocols for disease surveillance. This allows nations to resolve potential conflicts diplomatically before they escalate, with organizations such as the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) providing platforms for scientific-diplomatic engagement. Rather than being a purely cooperative effort, this is a strategic use of science to negotiate boundaries, responsibilities, and shared risk. Food safety and food security provide further examples of the diplomatic role of science. Disputes over food standards, trade, and agricultural practices can create tension between nations, particularly when health and safety regulations differ. Science Diplomacy here is used to harmonize these standards while respecting national sovereignty, thus preventing potential trade wars or diplomatic standoffs. For example, the Codex Alimentarius Commission, a joint effort by WHO and FAO, plays a diplomatic role in mediating disagreements over food safety, using scientific evidence to broker consensus on what constitutes safe food practices. In this capacity, science is not just enabling cooperation but is driving diplomatic negotiation, ensuring that trade disputes do not escalate into larger geopolitical conflicts by grounding them in neutral, scientifically verifiable standards. In the broader context of environmental issues like biodiversity loss and pollution, science is used to establish common metrics for environmental impact assessments, which then feed into diplomatic negotiations for treaties like the Convention on Biological Diversity or the Montreal Protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Science acts as a form of diplomatic currency in these discussions, allowing countries with divergent interests to engage in constructive dialogue based on mutually understood scientific principles. Diplomatic negotiations often hinge on the interpretation of scientific data, with science providing the means to translate complex environmental challenges into actionable policies, thus preventing potential conflicts over resource use and environmental degradation. In conclusion, the One Health approach is not just about scientific collaboration; it is a key arena for Science Diplomacy, where science plays a diplomatic role in shaping international policies, mediating disputes, and fostering global trust. By applying scientific principles in diplomatic contexts, nations can navigate the challenges of human, animal, and environmental health with greater clarity and consensus, ultimately leading to more effective and equitable global governance. In this sense, the diplomatic role of science in One Health goes beyond cooperation—it is about using scientific knowledge as a strategic tool to resolve conflicts, negotiate treaties, and build long-term, sustainable relationships between nations. About the author Casimiro Vizzini Science Diplomacy Consultant Health Diplomacy Alliance A Medical Doctor specializing in Urology, with advanced studies in International Cooperation, he has over 18 years of experience bridging science, health, and diplomacy. His career spans roles at UNESCO, where he led science policy and capacity-building projects, collaborated with the AAAS on science diplomacy, and secured European Commission funding for global partnerships. As Secretary General of EUGLOH, he advanced academic